Yesterday I attended a conference in DC on 'a transatlantic agenda for natural gas supply,' at the Johns Hopkins University School of Advanced International Studies, among mostly energy diplomats and scholars on geopolitical energy affairs. I was invited to a panel to discuss the question: shale gas, a game changer? Here are the remarks I made:

"I appreciate the invitation to be here today and the opportunity to share a couple of things with you. The question to this panel is: “Shale gas: is it a game changer?” Has anyone ever asked which game? If the game is energy security, the answer should most likely be yes. For the United States that game has already changed, with spillover effects to Europe. The estimates for resources that are technically recoverable are huge. However, as one gentleman mentioned earlier today, “the problem with shale gas is that it is gas” - it releases carbon when burned. Due to limited fossil resources, energy security and reducing carbon emissions were two sides of the same medal, but with so many new discoveries of fossil fuels made, the two problems are less and less aligned. Climate change is becoming ever more urgent, while finding alternatives for dwindling fossil fuel reserves is much less pressing.

Let me make three points:

First: for natural gas to become the “bridge fuel” to a de-carbonized economy many promise it to be, additional policy is needed. “We need to steer it that way,” said Mr. Elkind (DOE) this morning. We need policy to really displace coal-fired power generation and incentivize renewable energy sources. Without such policies, increased supplies and lower prices will lead to more consumption with associated CO2 emissions, more than offsetting emissions savings due to a new preference for gas as the fuel of choice for new power generation. And, as we recently learned from the Cornell study on emissions from shale gas, capture or prevention of fugitive methane emissions is required. The Cornell study (Howarth, 2011) has many questionable assumptions and bad data, but one thing it tells us is that we can’t only look at the emissions from burning the fuel to compare it to alternatives like coal; we need to take into account the complete life-cycle.

To be a bridge fuel means to be able to reduce greenhouse gas emissions on the short term and facilitate a shift to zero-carbon technologies on the long-term. The first can be achieved by substituting natural gas for coal in power generation. MIT’s ‘Future of Natural Gas’ study (MIT, 2010) - as Ms. Kenderdine presented in this same room in February - has shown that there’s significant potential to do that here in the US. The second can be achieved by growing renewable sources, like wind and solar power. On their own, when they grow too big, their intermittency would cause problems on the grid, but with flexible natural gas plants as back-up power, larger shares of renewables are possible. However, as other studies have shown (Tyndall, 2011; RFF, 2009), without market interventions gas won’t play this double role. For gas to displace coal, a price on carbon could work. That would also help renewables. But if it’s not enough, additional incentives should be put in place (such as a strong clean energy standard (CES)). The larger point is that we need to think of natural gas within the energy system at large, go beyond gas-to-gas comparisons, discuss what role it has to play in the transition to an energy efficient, low-carbon economy, and make policy accordingly.

Oil & Gas interests had better lobby for such low-carbon policies than against them. The US is already losing the game that really matters, as China and Europe are pushing ahead with clean technologies. Gas should help the US free itself from its fossil fuel dependence, instead of staying stuck in it.

That brings me to my second point, which is about sustainable extraction, about the need to take a long-term perspective and look beyond the gas glut. As abundant as it may be, shale gas, and the jobs that come with it, are finite resources. Once the gas and the jobs are gone, no-one will ever be able to enjoy their services anymore. That holds true for all fossil fuels. If we’re talking about sustainable production of shale gas, we should not only look at good local environmental practices and short term reduction of greenhouse gas emissions. Sustainable extraction requires that part of the revenue from nonrenewable resources is invested in building a renewable substitute (e.g. Daly, 1990), so that the same level of services are available to future generations in a post-gas era. This means that revenues from gas extraction should be used to invest in renewable energy sources and green jobs, in good infrastructure, energy efficient housing, education and innovation. We all have a responsibility to communities and their heirs to prevent the mining-town boom-bust cycle.

My third point is that shale gas may be abundant, but is it really as cheap as we think? Already we see that shale gas production involves considerable social and environmental costs. They vary from place to place, and may not yet be institutionalized, but they are real. If it’s increased crime rates, split communities, water contamination, road degradation, industrialization of places of rural tranquillity or natural beauty, these costs are real and will eventually be factored in. Now they materialize as money spent on the PR battle and lobbying legislatures against stricter rules. They will become more institutionalized when permit fees are raised for stronger oversight and adequate permitting capacity at state departments, when new regulations with better safeguards for individuals, communities and the environment are adopted, and when new infrastructure, to treat waste water for instance, has to be built. Some say such costs will not be a show stopper, but a study by the Oxford Institute (Gény, 2010) estimated that in Europe production costs would be three times higher than currently in the US, which to a large extent is due to the more demanding regulatory context. ExxonMobil recently warned that any new government regulations on hydraulic fracturing could stop shale exploration (Reuters Africa, April 28, 2011). That should be a hint. Could it be that the US is experiencing a “shale bubble”?

To conclude, I hope that - in addition to the energy security and zero-carbon game - shale gas can become a game changer on a third playing field: the way we do business in the public domain. I hope the hydraulic fracturing PR debacle will teach lessons on more cooperative, 21st century decision-making. Instead of door-to-door lease acquisition, why don’t businesses invite NGOs to the table and help organize communities to start a dialogue about sustainable shale gas extraction, and allow time for a consensus to emerge? Failing to do so will get less and less done. When governments see their ability to safeguard public and environmental health compromised by huge debts, more of that responsibility befalls private parties."

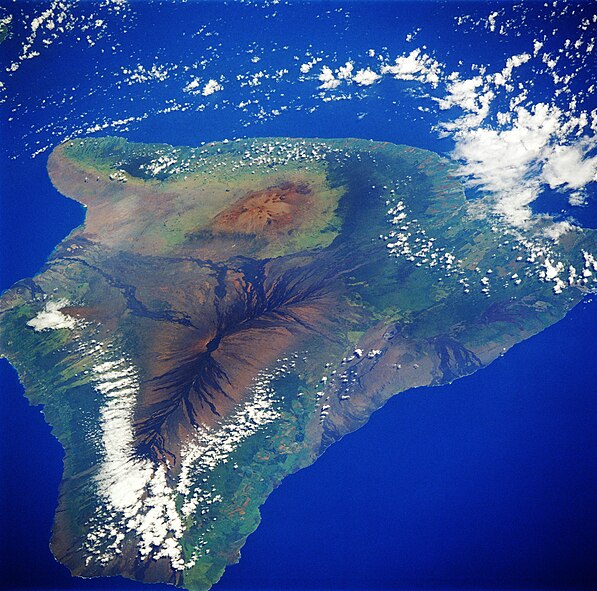

For the first time I did not spend Christmas in a wintery location with family. Instead, Christmas passed while Merijn and I honeymooned on Hawaii, on the Big Island. Hawaii is a dream destination, one that had spoken to my imagination ever since I saw a film about Hawaii in the Omniversum theater in The Hague with my brother and father. That must have been in the late nineteen-eighties. In my memory it was about the jungle and full of loud sound effects, prompting my brother and me to rename it "Lawaai," which is dutch for loud noise. And now I've been there, in the middle of the Pacific. Here's a list of things that made Hawaii special, in no particular order:

For the first time I did not spend Christmas in a wintery location with family. Instead, Christmas passed while Merijn and I honeymooned on Hawaii, on the Big Island. Hawaii is a dream destination, one that had spoken to my imagination ever since I saw a film about Hawaii in the Omniversum theater in The Hague with my brother and father. That must have been in the late nineteen-eighties. In my memory it was about the jungle and full of loud sound effects, prompting my brother and me to rename it "Lawaai," which is dutch for loud noise. And now I've been there, in the middle of the Pacific. Here's a list of things that made Hawaii special, in no particular order: